Landlords may grow rich as they sleep, but there’s no rest for the tenant who must pay rent or get thrown out on the street.

Earlier this year, a photo showed up in the Reddit forum r/ABoringDystopia showing a Chase Bank marketing poster. The poster read simply, “Landlords grow rich in their sleep. – John Stuart Mill”. It sure made landlording sound like a pretty sweet gig. In the great marketing tradition of not telling the whole story, though, Chase left off the rest of Mill’s words, arguably mangling the sentiment beyond anything the author would have recognized as his original thought.

The missing context, if you’re curious, goes like this. “The ordinary progress of a society which increases in wealth, is at all times tending to augment the incomes of landlords; to give them both a greater amount and a greater proportion of the wealth of the community, independently of any trouble or outlay incurred by themselves. They grow richer, as it were in their sleep, without working, risking, or economizing. What claim have they, on the general principle of social justice, to this accession of riches?” It’s from Book V, Chapter 2, Section 5 of Mill’s Principles of Political Economy with some of their Applications to Social Philosophy (1848). A dense read for sure, but density is no excuse for dishonesty.

While the best intentions of marketers are often dubious, thinking of this quotation reminded me of conditions at the bottom of the housing market. In 2010, the housing bubble had burst and the economy was full of people who needed homes but couldn’t afford them, and who, in fact, had often been foreclosed upon. It was also full of vacant foreclosed houses, structures which, if they were to keep their value instead of decaying into uselessness, would need to be tended and occupied, soon. Everyone with eyes and a brain could see that this problem situation had a clear and humane solution: reuniting people and homes. But how, when people were broke? It seemed economically unworkable, short of a homegrown peasant revolution.

By 2012, the federal government stepped in. They incentivized the sector of the economy where money was accumulating – Wall Street – to buy up empty homes, maintain them, and rent them out to those who needed a place to live. Their intentions seemed good, pairing people with homes and stabilizing the housing sector, but parasites gotta suck blood somewhere.

Between 2007 (the crash) and 2017, rental households grew by 6.5 million in the U.S., while additional owner-occupied homes grew by less than a million. With rent money pouring in, corporate landlords began cutting corners. Responsibilities like fixing toilets and broken windowpanes were shifted onto tenants, as well as landscaping maintenance. Some rental companies insisted that tenants buy insurance that covered the structure itself in addition to their own belongings. And of course, it became harder to contact distant, corporate landlords for any reason, especially getting the security deposit back.

Apologists for the rentier class claim that landlords provide a valuable service by providing and maintaining properties where less affluent people can live. (And they do provide housing, in much the way scalpers provide tickets.) However, if they’re not doing the maintenance, and they’re charging rent and fees over and above the purchase price and upkeep (for a house the renter will never own), the only “service” being provided is to shareholders. John Stuart Mill must be gyrating in his grave.

Since the pandemic, insult has joined injury, with rents getting more expensive in almost all markets. With more homes being snapped up by investors instead of families who intend to occupy the house themselves, would-be residents are getting priced out of the market. Rising wages and the ability to work from home sent more affluent buyers shopping in cheaper markets, too, bidding prices up too high for those who are committed to the area. According to data that the New York Times obtained from Zillow, the average worker has to toil for almost 63 hours per month just to cover the average $2040 rent, six hours longer than in October, 2019. There is no end in sight.

Which brings us back to Chase. JP Morgan Chase is quite possibly the world’s largest bank, and now, they’re partnering with Haven Realty Capital to drop a cool billion dollars to build single-family rental properties around the U.S., starting in the Atlanta metropolitan area. This is being touted as the solution to a housing market where people can’t afford to buy homes, but still need to live in them. A solution which, mind you, will allow JP Morgan Chase shareholders to grow rich while they sleep, while renters pay as much as the market will bear, perhaps never able to save enough for a home of their own. What claim have corporations and banks, on the general principle of social justice, to this accession of riches?

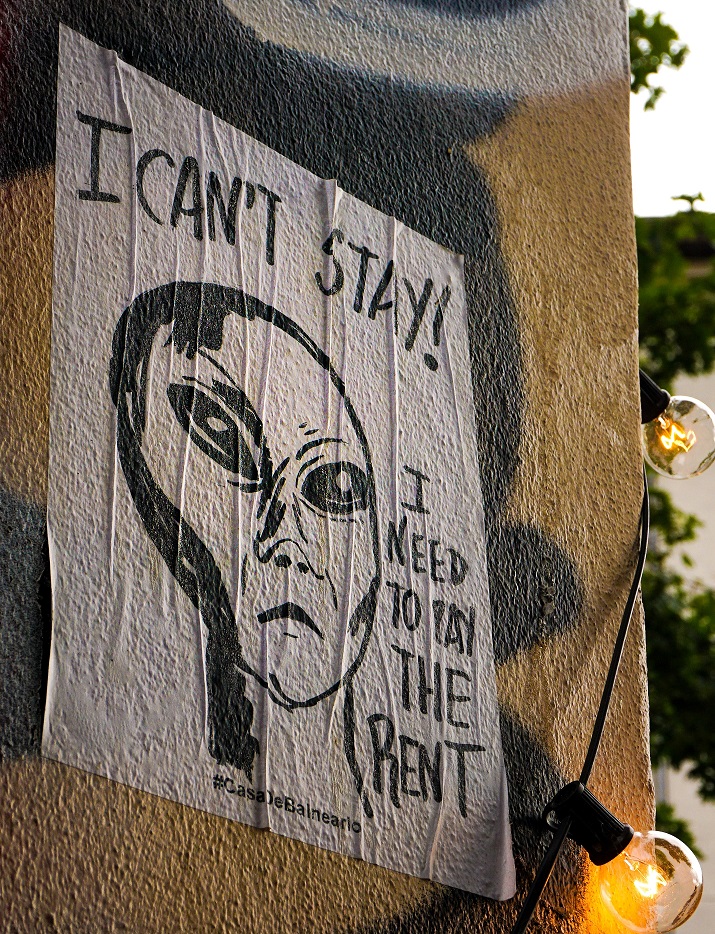

Used to be that homes were built for people to live in. Now, they’re built for as much profit as can be extracted from people who have a basic biological need for shelter. Perhaps one day, these warm-blooded meat-based profit generators will fight to become people again. But not now; we have to get to work to afford the rent.

Related: The Housing Bubble and its Discontents

Sources:

Big banks using heavily edited John Stuart Mill Quotes in their advertising.

Principles of Political Economy with some of their Applications to Social Philosophy

When Wall Street Is Your Landlord

Landlords as Stewards of Housing Stability

More of Your Paycheck Is Going to Pay Rent. Which Cities Are Keeping Pace?

Join the conversation!