The federal agency cuts FoodNet monitoring, raising concerns over weakened foodborne illness tracking.

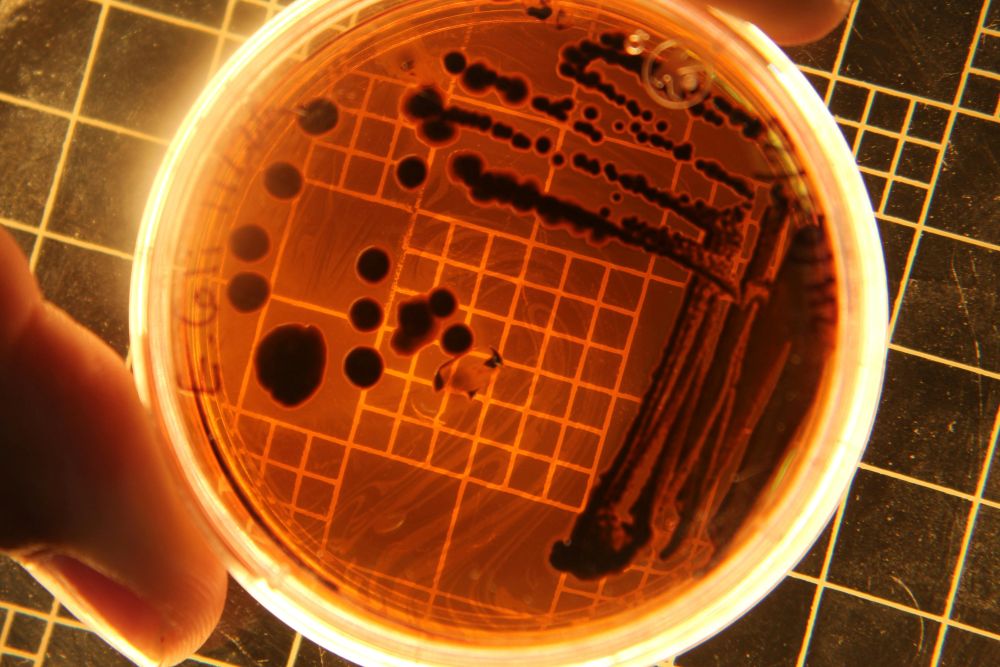

A federal monitoring system that tracks foodborne illnesses has been significantly reduced, a move that experts say could affect the nation’s ability to spot outbreaks early. The Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, known as FoodNet, is now focused on only two pathogens: salmonella and a dangerous strain of E. coli called STEC. Until July, it tracked eight different pathogens linked to foodborne illnesses.

The change happened quietly on July 1. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, FoodNet no longer requires participating states to monitor infections caused by campylobacter, listeria, shigella, vibrio, Yersinia or cyclospora. These bacteria and parasites can cause serious foodborne illnesses, particularly in pregnant women, newborns and people with weakened immune systems.

The decision has raised concerns among food safety specialists. For decades, FoodNet has been regarded as a reliable system for gathering detailed information about foodborne illnesses. It was created in 1995 as a collaboration among the CDC, the Food and Drug Administration, the Agriculture Department and health agencies in 10 states. Its coverage area includes parts of California and New York as well as states like Colorado, Georgia and Minnesota. Together, these regions represent about 16% of the U.S. population.

Experts fear that narrowing the program will make it harder to understand how widespread certain illnesses are and whether cases are increasing. “CDC is stepping away from one of its strongest systems,” said Dr. J. Glenn Morris of the University of Florida, who helped design the network in the 1990s. He warned that without active tracking, public health officials could miss trends and struggle to respond quickly when outbreaks happen.

A CDC spokesperson confirmed that the changes are tied to funding. Internal documents show the agency told state officials that budgets have not kept up with the cost of operating FoodNet at full capacity. While other national systems still collect some reports, they largely depend on states to send data rather than actively searching for infections. This makes FoodNet unique — and why its downsizing is worrying advocates.

Barbara Kowalcyk, a food safety expert whose child died from an E. coli infection two decades ago, called the decision disappointing. She said years of progress in improving food safety could be lost if systems like FoodNet shrink. Federal budgets for food safety have remained nearly flat, which means programs are stretched thin. For 2026, the CDC requested $72 million for food safety — the same amount it has asked for in past years.

Some officials fear the change could lead to fewer regulations down the road. “If you stop looking for foodborne disease, you can act like it doesn’t exist,” Morris said. “That opens the door to rolling back rules meant to protect people.”

The White House issued a statement saying the health and safety of Americans remains a top priority and that agencies will continue working together to protect the food supply. Still, how states respond remains unclear. Some, like Maryland, plan to keep reporting all eight pathogens. Others, such as Colorado, say they may scale back if funding drops further.

The future of FoodNet will likely depend on resources and political will. For now, its reduced scope marks a major shift in how the U.S. monitors foodborne illness — and raises questions about whether less oversight could mean more risk.

Sources:

The CDC quietly scaled back a surveillance program for foodborne illnesses

Join the conversation!