Focused ultrasound before chemotherapy improved survival for patients with glioblastoma.

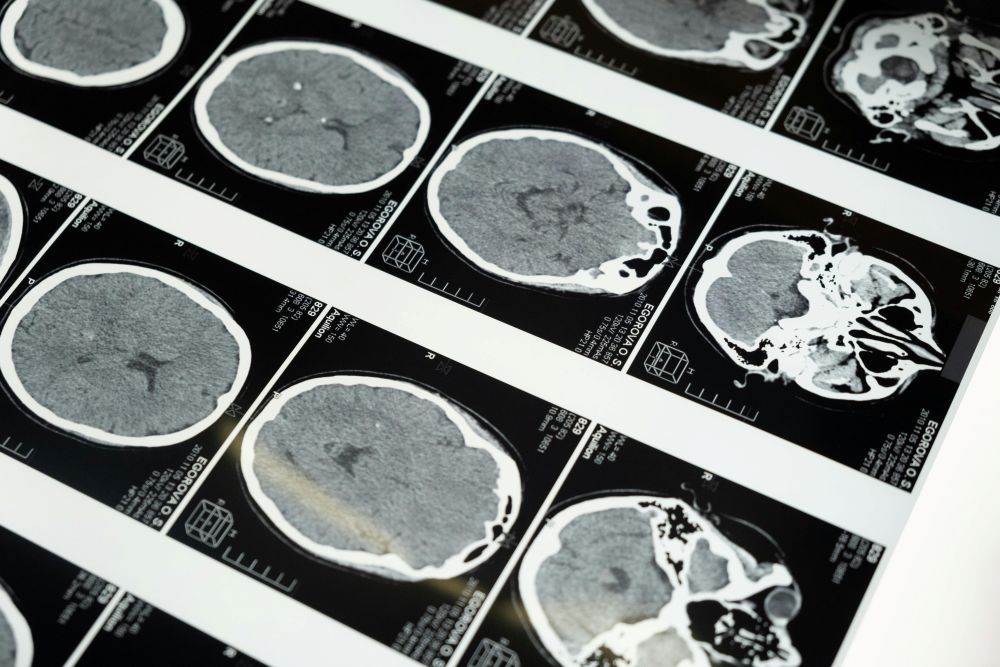

The latest research from teams at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and several partner sites has drawn attention because it suggests a new way to help people living with glioblastoma, the most aggressive type of brain cancer. In a trial that included 34 patients, doctors used MRI-guided focused ultrasound before giving standard chemotherapy. Patients who received this added step lived noticeably longer than a large group of similar patients who received only standard treatment. While the sample was small, the results were strong enough that many in the field are watching closely.

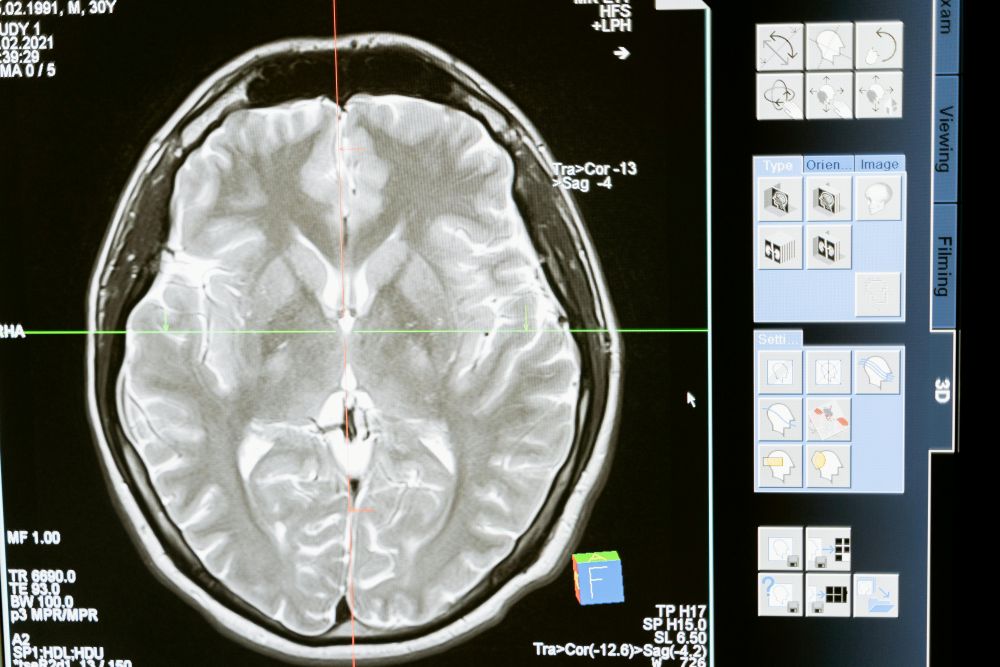

Every patient in the trial had already undergone surgery to remove as much of the tumor as possible. In glioblastoma, surgery is only part of the process because tiny cancer cells almost always remain. After surgery, patients usually start chemotherapy and radiation. In this study, some patients also had focused ultrasound treatments spaced out over several months. This technique temporarily opens the blood-brain barrier, a natural protective shield that blocks many substances—including most medicine—from entering the brain. The barrier is helpful for preventing infection but makes treating brain cancer extremely difficult.

Temozolomide, the most common drug used for glioblastoma, is known to reach the brain in small amounts. Past research has shown that less than a fifth of the drug makes it through the barrier in most cases. By opening this barrier for a short window, doctors hoped more of the drug would reach the areas around the tumor where lingering cancer cells hide. The new results suggest this may be happening. Patients in the focused ultrasound group went almost 14 months before the cancer began to grow again, compared to eight months in the matched control group. Their overall survival was also longer, averaging more than 30 months compared to 19 months in the control group.

The technique involves injecting tiny gas-filled bubbles into the bloodstream. While the bubbles move through the brain’s blood vessels, doctors use MRI guidance to target specific regions with low-intensity ultrasound. The sound waves make the bubbles vibrate in a way that loosens the tight walls of the blood vessels for a short period. Once the barrier opens, chemotherapy can reach the tumor bed more easily. After a brief time, the barrier closes again.

Another promising part of this trial involved blood tests. Because the barrier was temporarily opened, cancer-related materials—such as DNA fragments and proteins—entered the bloodstream in small amounts. These markers helped doctors tell how each patient was doing over time, which may reduce the need for invasive procedures in the future. Similar tests are common in other cancers but have rarely worked in brain cancer until now.

Glioblastoma is known for its poor outcomes, even with aggressive treatment. Most patients live a little over a year after diagnosis, and the cancer almost always returns. For this reason, any improvement draws interest. Doctors involved in the study say these early findings may lead to new ways of pairing focused ultrasound with either standard drugs or drugs that normally could not reach the brain at all. Future trials are expected to explore these possibilities.

Sources:

Focused ultrasound combined with chemotherapy improves survival in glioblastoma patients

Join the conversation!