Bougainville voted overwhelmingly for self-determination, but they may not get the independence for which they fought so hard and so long.

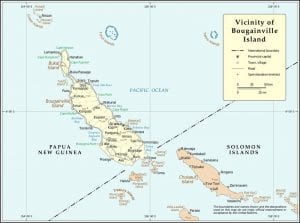

Late last year, voters in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, currently part of Papua New Guinea (PNG), voted overwhelmingly in favor of independence. The South Pacific island is home to roughly 300,000 people, and during the three-week referendum period, eligible Bougainvilleans rocked the vote with 85% turnout. Of those, 97.7% cast a vote in favor of self-determination and home rule. When the final tally was announced, blowing away analysts’ expectations, excited gatherings of voters cheered.

The problem? It’s a non-binding resolution, and there’s no deadline for working out the details. They may not get the independence they’ve wanted, fought, and died for, for decades.

Like many colonized people, Bougainvilleans long watched others extract their natural wealth and leave ruin and poverty in their wake. In 1967, PNG approved construction of the Panguna gold and copper mine by an Australian firm, itself a subsidiary of a British company, Rio Tinto. At the time, Panguna was the largest copper mine in the world, accounting for nearly half of PNG’s export income during the 1970s. Revenue from the mining venture didn’t benefit the Bougainvilleans much, but the mine itself displaced their homes and polluted the waterways that provided drinking water and fish they needed for food. Even though the mine is now closed, the ecological mess it made will remain for generations.

During the late 1980s, this intolerable situation reached a boiling point. The story of the popular insurgency that arose on the island is told in the hour-long movie The Coconut Revolution. Demands for independence, to close the mine and pay damages to the people, were laughed at and denied. Working with what they had on hand, the people of Bougainville constructed weapons, scavenged explosives from the mining operation, and after a blockade was imposed on the island, they grew their own food and even figured out how to fuel a limited number of vehicles with homegrown coconut oil. Hostilities ended when PNG hired British mercenaries to slaughter the ersatz Bougainville Revolutionary Army, prompting their own fighters to mutiny. The nine year long war had claimed the lives of 20,000 people, then about 10% of Bougainville’s population.

After the war came a peace deal brokered by Australia and New Zealand. The agreement guaranteed greater autonomy for Bougainville and a nonbinding referendum on independence by 2020, hoping this, combined with revenue-sharing, would satisfy Bougainvilleans and increase loyalty to the government in PNG. Clearly, this did not pan out as planned. The final say ultimately lies with PNG’s parliament. Bertie Ahern, an official overseeing the referendum, doesn’t believe that the Bougainvilleans are ready for full independence. Internally, Bougainville is split between factions who want their current President to stay in power and provide experienced leadership through the transition, and those who say Presidents ought not serve three terms, despite there being no clear successor to the incumbent, John Momis. Externally, Bougainville is sure to face challenges from China and other regional players who have an interest in re-opening the copper mine.

Indigenous resistance to colonial rule and resource extraction isn’t something we’ve left in the past. It’s a modern-day struggle, and Bougainville is not alone. The Wet’suwet’en People in northern Canada are fighting to block three pipelines from crossing their territory without their consent. Indigenous Saami people in northern Finland celebrated when a much-protested railroad project slicing across their land was shot down due to economic constraints. Independence movements and calls for self-determination are gaining ground internationally. This comes at a time when we must drastically reduce exorbitant levels of consumption and pollution in order to insure a livable world. Returning territory to Indigenous people who have an abiding interest in maintaining the integrity of their landbase is a deeply honorable way of insuring that those who come after us have something left to work with when their time comes to rebuild from our ruins.

Related: Extraction Has Victims

Join the conversation!